Put to the Ultimate Test – Part 2: Bending Tests by HELUKABEL

September 5, 2023

During the development of HELUKABEL cables and wires, they vigorously test each product in their testing laboratories. In the second part of their series, they will introduce you to bending tests.

In dynamic applications typical to mechanical and plant engineering or drive and automation technology, cables and wires are frequently subject to mechanical bending stresses. Although these stresses also occur in static installations, they are much higher in dynamic applications because the force and direction of movement are constantly changing. Such situations are pure stress for the cable. The wires, conductor insulation and jacketing material are squeezed on the inside and stretched on the outside, and the cable can tear. Degradation, up to and including cable damage, leads to faults and functional failures.

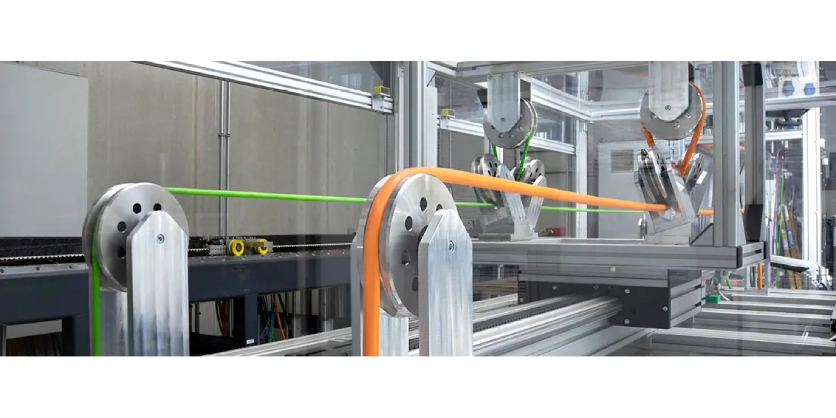

To make sure their cables and wires reliably withstand day-to-day stresses, HELUKABLE perform bending tests on them in their testing laboratories. These tests are normally laid down in the specifications from customers or in standards such as those from the VDE. Their testing equipment simulates bending stresses with diverse loads and bending radii in order to verify the mechanical strength of the cable. Their test methods include alternate bending tests using two rollers (as per DIN EN 50396 6.2) and three rollers (as per DIN EN 50396 6.3). Parameters such as speed, acceleration and traverse path can be easily varied to create realistic test conditions for a diversity of use cases.

Every cable they develop must comply with the strict test criteria. The copper wires, insulation material and jacketing material must show no signs of degradation after testing. Moreover, the entire stranding as well as braiding and twisting must maintain their original form. Only in this way can it be guaranteed that the cable will function reliably in day-to-day use, even after millions of bending cycles.

Even more, they have purpose-designed drag chain tests for cables used in drag chains. You can read about these in the next part of their series.

Click here to read more about the bending test equipment they use and the performance criteria they can evaluate.

Ask the expert

What is the minimum bending radius and what does this value tell me?

The minimum bending radius is the smallest possible radius to which the cable can be bent without damaging it. It is specified as a multiple of the cable diameter. The smaller the value, the more flexible the cable. There are several industry standards defining the minimum bending radii for different cable types. The values differ greatly, depending on whether the cable is used in a fixed or moving application.

A MULTIFLEX 512®-C-PUR UL/CSA drag chain cable, for example, has a minimum bending radius of 4 x Ø in a fixed application, but only 7.5 x Ø in moving one. The reason for this is that the bending stress in a permanently moving cable is significantly higher as the force and the direction of the bending motion are constantly changing. A suitable minimum bending radius is hence an important criterion when choosing cables and wires.

How can the flexibility of a cable be improved?

There are various ways to improve this, starting with using the best materials. In most cases, copper wires comprising of fine or finest stranded conductors are sufficiently flexible. Alloys can be used as well for some custom applications. Care must be taken that the insulation and jacketing materials are likewise flexible. The choice of materials makes a big difference, especially in applications at extreme temperatures. PUR or TPE jacketing are suitable for cold temperatures as they don’t get very stiff. The diameter and construction also have a major impact on the cable’s bending properties. The shorter the lay length, i.e., tighter twisting inside the conductor stranding, the more flexible the cable.

More Information

Related Story

Put to the Ultimate Test – Part 1: Torsion Tests by HELUKABEL

Cables and wires in industrial robots and other moving machine parts are often required to withstand extreme stresses caused by torsion. Constant repetitive movements put materials under considerable strain. At the same time, operators expect components to function perfectly and reliably throughout their entire service life to avoid disruptions, outages and safety hazards.